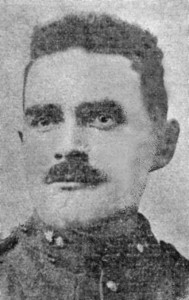

A stained glass window in the south west wall of the LaSalette Church pays tribute to the memory of Pte. Francis Leland Murphy. Francis was born in 1885 in Silver Hill to John and Elsie Forbes Murphy. He enlisted in the 133rd on February 9, 1916 indicating he had been a member of the 39th Militia and was a farmer. He was also college educated and an accomplished writer who sent a steady stream of letters home to the Simcoe Reformer describing their days in training at Camp Borden and later in England. Francis and his friend, John Carnaham of St Williams, were placed in the 29th Battalion, British Columbia. John was killed on April 9, 1917 at the battle of Vimy Ridge. It had a profound impact on Francis. He would write a heart rendering story of how he visited a church and asked M. le Cure for some of his red roses to lay on his friend’s grave. Francis was killed in action four months later on August 21 at the Battle of Hill 70. He has no known grave. His name is inscribed on the Vimy Memorial and on the window that reflects the sorrow of a grieving family.

A stained glass window in the south west wall of the LaSalette Church pays tribute to the memory of Pte. Francis Leland Murphy. Francis was born in 1885 in Silver Hill to John and Elsie Forbes Murphy. He enlisted in the 133rd on February 9, 1916 indicating he had been a member of the 39th Militia and was a farmer. He was also college educated and an accomplished writer who sent a steady stream of letters home to the Simcoe Reformer describing their days in training at Camp Borden and later in England. Francis and his friend, John Carnaham of St Williams, were placed in the 29th Battalion, British Columbia. John was killed on April 9, 1917 at the battle of Vimy Ridge. It had a profound impact on Francis. He would write a heart rendering story of how he visited a church and asked M. le Cure for some of his red roses to lay on his friend’s grave. Francis was killed in action four months later on August 21 at the Battle of Hill 70. He has no known grave. His name is inscribed on the Vimy Memorial and on the window that reflects the sorrow of a grieving family.

Pte. Francis Murphy’s Tribute to John Carnahan

I will now tell you of an incident of the war. France is a beautiful land now, of sunshine and flowers, roses everywhere. I called upon the village cure one Sunday and said, “M. le Cure, I have come to beg a few of your roses.” “Sit down, monsieur, and tell me why you want my little pets, for I love them, you know,” he replied. So seating myself I began to tell him of the cold morning in January when John Carnahan and I drove to the residence of the late Matthew McDowell and enlisted in the 133rd.

“It is for his grave, Messieur?”

“Yes father.”

“Oui, oui. Certainly, you shall have them, Marie!” he called, and a little maid came running armed with shears.

I protested, but such a bouquet! The old cure reached for his hat. “I will accompany you.” “No, no, M. le Cure, the way is long.” “Au, yes; you will permit me. My pleasures are few now,” I thought of the long vigils he had, of his years, for his hair was flowing white. Yet the sturdy old man now takes the place of five priests at the front.

“One moment,” called Marie, and away she ran, and I wondered why, but we were not long on our way when a score of young girls caught up to us, laden with roses, and with them Marie. Some time after we all reached the 14th Battalion’s burial plot. There are eighty-four graves, all marked and numbered, with a cross over all, with a brass plate bearing each name – sixteen of them 133rd boys. And so I had roses enough for all of Norfolk’s Own, while one tall young lady worked upon a lovely wreath, which she placed upon the cross and knelt down. We all followed her example while the old cure prayed. I remember his faltering English.

“And may these brave men, and all others who fall in the cause of Liberty, Justice and Right, through Thy mercy, Lord, find a place of refreshment, of joy, and peace, through Christ, Thy Son, our Redeemer, Amen.

I rose and looked over that shell torn ground of the valley of death. It looked to me as though some giant’s plough had torn it asunder and after it an earthquake had torn great chasms here and there. The girl clung to the cross, sobbing bitterly, and her comrades trying to comfort her.

“See, M’sieur,” said the priest, “the bridal roses. Her brother first, and now her lover have fallen for France, and she has brought for your comrade the roses intended for her wedding day.”

I went to her speaking in French. “I understand and appreciate your remembrance of the stranger dead. No greater honour could you have shown than this.” But I got no further. The maiden rose and gave me an embrace and a kiss -a sister’s kiss – as is the custom of France, and something was thrust into my puttee. I stood dumfounded, while the maidens seemed to melt away.

The cure drew a poniard from my puttee. “See, monsieur, she has made you her knight and her avenger, for this poniard (very useful at close quarters in bayonet fighting) has been in her family since the Crusades. It belonged to a knight of France. And her colours, too, see.” He pointed to a blue ribbon with a medal around my neck.

I found my tongue at last. “Monsieur le Cure,” I began, I was her knight already, had she comprehended. Indeed, so is every Canadian soldier.” The maidens were coming around again. “We Canadians are brought up to love God and beautiful things, to respect and protect women, whosoever they are. Nothing can make a Canadian soldier fight harder than the thoughts of his dear ones at home.”

“I understand now,” said the old cure, after he had explained to his friends in French, “why Canada has conquered at Ypres, at the Somme and at Vimy Ridge. Oh, the good fight!”

So we wandered home, the priest and the old world and the new. It was in the gloaming now, and sweet indeed were the clover meadows and the roses; but sweeter yet to me is the thought that the women of France remember, even as our own.

Francis L Murphy, No. 797104 {The Simcoe Reformer, Aug. 16th 1917}